Island Artisans

Weavers * Artists * Musicians

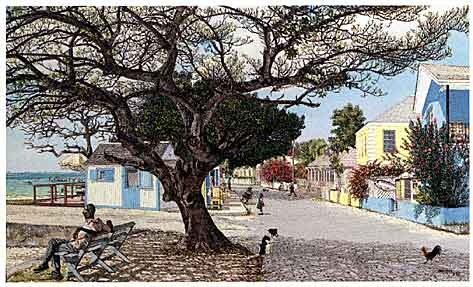

Miz Curline Higgs' workspace on Bay Street

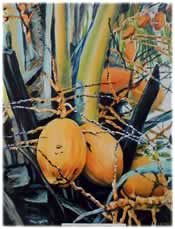

The art of straw work weaving is alive and well on Harbour Island and North Eleuthera. These baskets, hats, dolls and mats are made to be sold in the local shops and straw markets of Nassau, Freeport and overseas. Miz Curline Higgs, Miss Eva Mather, Sister Sarah Johnson and Miz Jacquelyn Percentie of Harbour Island are a few of several local artisans who have mastered the art of weaving these beautiful items, and who continue to sponsor up-and-coming younger weavers from the neighboring settlements as they continue the tradition.

Traditional technique

To create weavable strips, the straw is taken from the top of the palm frond. The frond top is cut and stripped, then hung from trees for up to four days. These are then laid flat to dry for another four days. The fully-dried strips of pond top are cut into thinner strips. Before the strips can be used, they are soaked in salt water for an hour and then wrapped in cloth for another hour. This makes the straw pliable and useful for weaving. The straw is wrapped around the stalk from the pond top and woven into various household items such as hampers, picnic baskets, cake tops, place mats, napkin holders and even baby carriers. The more popular items are the picnic baskets and place mats.

Local Galleries ...

Princess Street Gallery, Charles Carey

Briland Brushstrokes, Harvey Roberts

Local Music ...

Hogheads

Native Sons

Snapshot Band

Eleuthera Express

Chico Johnson

BRILAND MUSIC, YESTERDAY & TODAY

From the musical stylings of yesterday's Diatones and the Coral Sandpipers to today's Courage Band, Native Sons, Hogheads, The Funk Gang [aka The Brilanders], James Major and Ithalia Johnson, the music of Harbour Island tells the compelling story of its history. Whether playing reggae, merengue, pop, calypso, soca, gospel, steel pan or rock music, these performing groups continue to develop the Harbour Island 'island music' sound As a matter of fact, these contemporaries all share two key musical influences in particular: The Percentie Brothers and Junkanoo.

THE PERCENTIE BROTHERS

The music of the Percentie family is now in its fourth generation, thanks to the latest revival of 'Native Sons' in 2000. "Papa" Percentie [1889-1963], a natural musician, farmer and part-time preacher at the Church of God on Chapel Street gave the original Percentie Brothers, born and reared on Harbour Island, their basic interest in music. He gave the island its spiritual favourite, "Heaven Is So High.". Their collection of songs has been built up over a period of decades. Herman, the oldest of the brothers and the nominal leader of the band, plays the banjo. Victor served as the lead singer and guitar. The melodious voice best featured in 'Zelma Rose' is Anthony ["Tony"], second guitarist. Newcomers to the band seeing them perform for the first time were fascinated by the fourth instrument referred to in 'Briland Rumba' as a 'can.' These ingenious ** if not entirely original ** instruments, made up of a ten-gallon can, a broomstick, a hard-woven cord and a second joint of hambone, effectively supplied the string bass background music. Newton Percentie, Herman's son, slapped the one string of the 'can' with a flare reminiscent of professional bass players. Their albums 'Harbour Island Sings,' 'Songs in Calypso' and 'Songs in Goombay' were first produced in 1953, and have been re-released several times. 'Harbour Island Sings' in particular is the island's first album ever produced in full stereo.

Interestingly enough, the element of love is almost entirely missing from the usual traditional calypso tunes found on Harbour Island. A Percentie Brothers contemporary, Rudolph 'Dykes' Albury, gave the island 'Lita,' a catchy rumba that is well-known as a rare Bahamian love song. But because so much of Bahamian calypso is of indefinite origin, Briland is particularly proud of 'Zelma Rose' and 'Briland Rhumba,' with words and music by Humphrey Percentie.

JUNKANOO

Junkanoo, a hybrid of Afro-Bahamian music and dance, began with the slaves who were given three days off at Christmas. In the early days, it involved groups of grotesquely masked dancers and musicians travelling from house to house, often on stilts. In one form or another, the practice became popular in the Carolinas, Jamaica, British Honduras [now Belize] and The Bahamas. Junkanoo went into decline after slavery was abolished, and became all but extinct in areas of the Caribbean where it once flourished. The Bahamas alone kept the memory alive, and is now the only country to continue the tradition in an annual festival of national significance.

The music has changed little since the early days, with goatskin leather drums, cowbells and whistles, and improvised homemade instruments such as bicycle horns, wheel rims and conch shells making up the sound. The drums were traditionally wooden barrels cut in half with goatskin stretched across one half that must be "tuned" by burning paper or candles under the tightly-stretched skin. Junkanoo remains the most distinctive, individual expression of Bahamian art and culture.

Harbour Island [Dunmore Town] is a small settlement on the outer fringe of the Bahama Island group. Situated some sixty miles northeast of Nassau, it is one of the oldest and most colourful of the Out Islands. It was the capital of the Bahamas for a short time in the early days before the British succeeded in terminating organized piracy and established the present government in Nassau. Harbour Island has retained its natural charm, and the people their quiet dignity.

Local Artists

Larry Cleare

Charles Strachan

Obie Goodman

J. Bethel

Dorothy Rahming

Allie Mather Percentie

SKA,

REGGAE AND DUB MUSIC |

For decades, beginning in the 1920's, the dominant music in the Caribbean was Trinidad-based calypso . The lilting, topical and frequently risqué songs were initially sung in an African-French patois but began to switch to English as the music began to attract the interest of American record labels such as Decca and Bluebird.

Post World War II saw the emergence of various Caribbean music forms, notably steel-pan music of Trinidad and Tobago. In the late 40's and early 50's, Jamaican musicians began combining the steel-pan and calypso strains with an indigenous mento beat (e.g. Harry Belafonte - Jamaica Farewell).

During the 1950's Jamaican youth was turning away from the American pop foisted on them by Radio Jamaica Rediffusion (RJR) and the Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation (JBC). Weather conditions permitting they listened instead to the sinewy music being played on New Orleans stations or Miami's powerful WINZ, whose playlists included records by Amos Milburn, Rosco Gordon and Louis Jordan. Significant New Orleans artists of the time included Fats Domino, Jelly Roll Morton, Champion Jack Dupree and Professor Longhair. It is surmised that the delay effects which are an important part of the reggae/dub sound may have initially been inspired by the oscillations in the signal from these far away radio stations.

During this period, Jamaican bands began covering U.S. R&B hits, but the more adventurous took the nuts and bolts of the sound and melded them with energetic jazz conceits - particularly in the ever-present horn section - and emerged around 1956 with a hybrid concoction christened ska . Ernest Ranglin, the stellar jazz-rooted Jamaican guitarist who backed up the Wailers on such ska classics as "Love and Affection" and "Cry to Me," says that the word was coined by musicians "to talk about the skat! skat! skat! scratchin' guitar strum that goes behind."

Practically overnight, ska spawned a major Jamaican industry, the Sound System , whereby enterprising record shop D.J.'s with reliable U.S. connections for 45's would load a pair of hefty P.A. speakers into a pickup truck and tour the island from hilltop to savanna, spinning the latest hits. D.J.'s also gave themselves comic book nom de plumes like Prince Buster and Sir Coxsone Downbeat. Competition grew so heated that D.J.'s covered up labels or scratched them off so that rivals couldn't keep up with the latest sounds.

The ska craze spread to London in the late 1950's and early 1960's and in the United Kingdom ska soon came to be labelled bluebeat . This music would probably have remained a mere curiosity were it not for the efforts of a white Anglo-Jamaican of aristocratic lineage named Chris Blackwell. As a hobby-like business venture he had set up a small scale distribution network for ethnic records but he had a vision about the potential appeal of Jamaica's oscillating answer to the blues. In 1962 Blackwell took his tiny Blue Mountain/Island label to England, purchased master tapes produced in Kingston and released them in Britain on Black Swan, Jump Up, Sue and the parent label Island. Initial artists included Jimmy Cliff, the Skatalites and Bob Marley.

In England Blackwell struck up a synergism with the fashion conscious mod and skinhead teenage movements through his seminal Jamaican rock records. His big breakthrough came in 1964 when Millie Small, one of the artists he managed, had a huge U.S. hit with "My Boy Lollipop."

Back in Jamaica "stay and ketch it again" became the rallying cry of Sound System ska. Soon every "Rude Boy" (ghetto tough) and country orphan wanted to hear his own voice barrelling out of a bass speaker. The Wailer's first single "Simmer Down" was a ska smash in Jamaica in late 1963/early 1964 and called on the island's young hooligans to control their tempers.

The ska-bluebeat advance into what became rock steady occurred around 1966. James Brown and funky U.S. stuff was cited by Bob Marley as an influence for "de young musicians, deh had a different beat - dis was rock steady now! Eager to go! Du-du-du-du-du... Rock steady goin' t'rough." Marley was right on target when he linked James Brown with the transition, since R&B was to ska what soul was to rock steady.

As far as Jamaican record buyers were concerned, the origin of the word reggae was the 1968 Pyramid single by Toots and the Maytals "Do the Reggay" (sic). Other possibilities as to the origin of the word include Regga, the name of a Bantu speaking tribe on Lake Tanganyika and a corruption of "streggae," which is Kingston street slang for prostitute. According to Bob Marley, the word is Spanish in origin, meaning "the king's music" but according to veteran session musicians the word is a description of the beat itself. Hux Brown of the Skatalites and lead guitarist on Paul Simon's 1972 hit "Mother and Child Reunion" says that it is "just a fun, joke kinda word that means ragged rhythm and the body feeling."

By the 1970's, the U.S. top 40 hosted several rock steady and early reggae hits, most notably Desmond Dekker and the Aces anti-colonial diatribe "Israelites" (1969), Jimmy Cliff's "Wonderful World, Beautiful People" (1970) and Paul Simon's "Mother and Child Reunion" (1972), recorded in 1971 at Dynamic Studios, Kingston. This track in particular helped spark a lively and lucrative cross fertilisation among prominent rock, R&B, punk, disco, funk and New Wave artists during the 1970s and early 1980s.

During 1970 and 1971 a jumble of Wailers singles were fed to the Jamaican audience backed by dub and "version" mixes of the A side. Osbourne "King Tubby" Ruddock was one of the originators of dub. While working as a selector for Duke Reid's Sound system and for Treasure Isle studio, he began using a dub machine to eliminate vocals from test cuts of a two track single, getting a private charge out of the way the rhythms - in the space of a microsecond - seemed to snap, crackle and then pop like a champagne cork when they had no vocal track to soften them. Equally exciting to him was the abrupt reintroduction of the complete mix "Jus' like a volcano in yuh head!" Tubby would say.

Springing the effect on a crowded dance hall one evening to blow a few minds (and possibly some speakers -since he liked the prankish ploy to be loud), the "dub-out" stunt was received like a revelation on high. It soon became an essential novelty at the larger jump-ups and then a standard fixture. Everybody began to examine the dub versions closely to determine whether Kingston rhythm sections held their own when stripped naked. Tubby added echo and reverb at ever more erratic intervals to enhance the "haunted house" effect of the stark trompings and backbeats going bump in the tropical night.

By late 1971, Kingstonians' appetites had been whetted for all-dub LPs and Lee Perry provided a remixed dub of Soul Revolution called Soul Revolution II. Perry eventually got so hooked on dub that he began layering sound effects (train whistles, running water, animal noises) on just about every old track he had in his possession.

The Wailers had been quite successful commercially in the Caribbean during most of Jamaican rock's evolutionary phases but after signing with Island records in 1972, they issued a string of well received albums on the internationally distributed Island label beginning with Catch a Fire (1973).

Bob Marley and the Wailers' mesmerising and often incendiary songs were customarily steeped in images of Third World strife and underscored by the turgid tenets of the Ratafarian faith as well as by symbols and maxims derived from Jamaican and African folklore. Rastas smoked "herb" to help with their meditations and the Rastafarian colours were richly symbolic:

The Wailers showed themselves to be much more than a mere Jamaican rock phenomenon as their music began to concern itself with social issues on the island but no one in Jamaica was prepared for the impact the music of Marley and company would eventually have world wide. In 1974 Eric Clapton reached the Number 1 spot in The United States and much of Europe with his version of Bob Marley's anguished shantytown confessional I Shot the Sheriff.'

Both Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left the Wailers in 1975 and have released numerous solo albums and from 1976 onwards, the Wailers concerts were invariably sellouts. Other Jamaican artists to achieve significant commercial success outside Jamaica during this period included Toots and the Maytals, Jimmy Cliff, Johnny Nash and Peter Tosh.

With the coming of punk and the subsequent new wave in the mid to late 1970s, Jamaican influences in music spread still further. In 1979 -1980 an eclectic new sound was introduced by interracial English groups like the Specials, Madness and the English Beat, which combined a ska revival with the antic energies of punk. Among the bands to emerge out of the new wave movement in Britain with reggae stylings were the Clash and the Police.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s the sounds of Jamaica were influencing many New Zealand artists including Coup d'Etat, the Screaming Meemees, the Newmatics, Dread Beat and Blood, Aotearoa and Herbs. Herb's French Letter was originally released in 1982 and re-released in 1995. to coincide with the French resumption of nuclear testing in the South Pacific.

Bob Marley died of cancer in 1981 and in 1987 Peter Tosh was robbed and murdered.

In England reggae influenced and dubby sounds have been transported into the 1990s by acts such as Dub Syndicate, African Head Charge, Jah Wobble's Invaders of the Heart and Natacha Atlas. Many of these acts fuse Jamaican influences with other sounds from around the world. Jamaican influenced music has mutated further through ragga and jungle into drum n bass .

The influence of ska, reggae and dub music is still strongly evident in contemporary music today as a new generation continues to evolve from the legacy handed down by the great luminaries such as Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and lesser known artists. Internationally, new artists like Ben Harper and Finlay Quaye display strong reggae influences in their work and New Zealand acts embracing these sounds today include the likes of Salmonella Dub and Pitch Black.

References

Barrow, S and Dalton, P. (1997). Reggae - the rough guide . London: Rough Guides.

White, T. (1991). Catch a fire: the life of Bob Marley . London: Omnibus Press.